Sikorsky CH-53

Sikorsky CH-53 user+1@localho… Mon, 11/22/2021 - 21:17 The CH-53 is a heavy transport helicopter that has been in continuous U.S. service since 1966. Multiple variants exist, powered by two or three turboshaft engines. The H-53 family includes...

The CH-53 is a heavy transport helicopter that has been in continuous U.S. service since 1966. Multiple variants exist, powered by two or three turboshaft engines. The H-53 family includes cargo, anti-mine warfare and combat search and rescue (CSAR) variants. As of the time of this writing, there are more than 260 H-53s in service in the U.S., Israel, Iran and Germany. Mexico and Japan are historical operators of the type.

Program History

In 1947, Gen. Alexander Vandegrift sought to retool the USMC for vertical assault operations from amphibious environments. The doctrine of employing large, concentrated amphibious formations – such as those used for Iwo Jima – was judged to no longer be feasible. Instead, mobile forces would have to be capable of rapid movement and dispersion to both survive and secure objectives. The Sikorsky S-56 (C-37 Mojave) was developed within this framework and was delivered to the USMC in January 1956. The Mojave quickly proved unable to fully realize the Marine Corps vision for vertical assault and the service quickly sought a replacement.

In Jan. 1961, the DoD issued a request for proposals (RFP) for a new vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) medium-lift platform to replace the Mojave, which was operated by the Army, Navy and U.S. Marine Corps (USMC). In March 1962, the USMC separately issued its own RFP for a C-37 replacement that was more suited to its requirements. The new RFP called for a helicopter capable of carrying 8,000 lb. (3,629 kg) outbound and 4,000 lb. inbound across a mission radius of 100 nautical miles (115 miles or 212 km) while cruising at 150 knots (172 mph or 278 km/h). Required payloads included 105 mm artillery, HAWK surface-to-air missile system, Honest John missile and 1 ½ ton truck and trailer. Additionally, the helicopter was to have a hover ceiling of 6,000 ft. on a standard day as well as a maximum speed of 160 knots (184 mph or 296 km/h). Three bids were submitted to the program:

- Sikorsky offered the S-65, leveraging its prior experience from the S-56 and S-64 Sky Crane (which would be the last helicopter design initiated by Igor Sikorsky). The S-64 in particular was optimized for heavy-lift missions, but for low speed and relatively short ranges. Sikorsky determined the rotor system of the S-64 combined with a clean-sheet airframe and GE T64 engines would closely match service requirements

- Vetrol offered its HC-1B (redesignated as CH-47A Chinook in July 1962). Just a year earlier in 1961, Vetrol had won a USMC development contract for the smaller CH-46 Sea Knight

- Kaman’s bid offered to co-develop the Fairey Rotodyne gyrodyne, an aircraft that takes off like a helicopter and flies like a conventional aircraft – but lacks tiltrotors

Sikorsky won the down-select in July and a development contract covering two prototypes for $9,965,635 million ($84.6 million in 2020 dollars) in September. Under the new tri-service designation system instituted in July 1962, the prototype was designated as the YCH-53A. The first prototype flew in on Oct. 14, 1964, and the first five production CH-53As were delivered in September 1966. The following year, the first CH-53As in would participate in combat operations in Vietnam.

Features & Variants

CH-53A

The CH-53A could fly twice as far, carry twice as much and arrive 50% faster than the preceding C-37 Mojave – matching or exceeding nearly all USMC requirements. The CH-53A could accommodate a payload up to 8,000 lb. or 38 troops internally or 13,000 lb. payload externally via a cargo hook. The A model had an empty weight of 23,500 lb. and a maximum take-off weight (MTOW) of 37,500 lb. – some 4,500 lb. more than the CH-47A. The CH-53A features a six-bladed main rotor based off of NACA 0012 airfoils as well as a rear four-bladed anti-torque rotor. The A model is powered by a pair of GE T64-6 turboshafts that weigh 713 lb. and are capable of producing 2,850 shp each. Upon entering service, the CH-53A was nicknamed the “Sea Stallion”.

HH-53B

The HH-53B is based off of the CH-53A and features a retractable aerial refueling probe, GE T64-3 turboshafts capable of producing 3,080 shp., jettisonable external auxiliary fuel tanks, recue hoist and three GAU-2B 7.62 mm miniguns (M134) – one machinegun mount on each side door plus one mount on the rear ramp door. The HH-53B/C was nicknamed the “Super Jolly Green Giant” as the successor to the preceding HH-3B “Jolly Green”.

HH-53C

The improved HH-53C was modified with 1,000 lb. of titanium armor, uprated T64-7 turboshafts, improved external fuel tanks and improved radios and avionics. The C model’s modifications made it an ideal platform for long-range penetration missions for special operation forces (SOF). The HH-53 fleet was later upgraded with the night recovery system (NRS), T64-7A engines and hover couplers to facilitate hovering directly over downed aircrew.

Five USAF HH-53Cs participated in the raid at Som Tay POW camp on Nov. 21, 1970, along with one HH-3. The helicopters ferried 56 U.S. Army special forces soldiers to the camp which was 23 miles West of Hanoi.

CH-53C

HH-53C derivative used by the USAF for cargo and SOF transport. CH-53Cs lacked the HH-53C’s armor protection and inflight refueling probe. However, the USAF subsequently ordered a number of armor and aerial refueling kits for its CH-53Cs.

CH-53D

The CH-53D was introduced into service in 1969 as an improved heavy transport. The D model was uprated with two GE T64-12 engines each producing 3,925 shp or 37.7% more power than the proceeding T64-6s. Sikorsky funded the development of new rotor blades in 1970. The design used SC1095 airfoils and was constructed with titanium spars bonded with nomex honeycomb pockets. The improved rotor blade (IRB) combined with the T64-12s raised the D model’s MTOW to 42,000 lb. The first IRB equipped aircraft flew in September 1971.

In an overload assault mission configuration, the D model could carry an external 12,742-lb. payload for 109 miles (175 km), hover for ten minutes, then proceed to unload the cargo and return with a 4,000-lb. payload internally. The engines were fitted with (EAPS) to mitigate the ingestion of foreign particles such as dust and sand into the engines.

RH-53A/RH-53D/MH-53D

The RH-53A and RH-53D are anti-mine countermeasure (AMCM) variants of the Sea Stallions operated by the U.S. Navy. RH-53As are converted from USMC A models while RH-53Ds were new-build airframes incorporating features from the CH-53D. The RH-53As were modified with rear mounts to tow anti-mine countermeasure equipment (AMCM), GE T64-413 3,925 shp turboshafts and rear-view mirrors.

The Improved RH-53D featured T64-415 turboshafts, improved flight control system, larger external fuel tanks and an aerial refueling probe. The AMCM equipment included tow cable and boom that could accommodate the SPU-1 magnetic pipe system or a variety of towed sleds. Mines would be detached from their mooring by the AMCM equipment, which would then be disabled by onboard gunners using 12.7 mm machine guns. The Navy used the RH-53D in a variety of general-purpose transport roles in addition to search and rescue. The RH-53D was subsequently redesignated the MH-53D.

CH-53E

Sikorsky extensively modified the D model to meet USMC requirements, in effect creating an entirely new helicopter. The resulting CH-53E is able to lift twice the payload of the D model while taking up only 1.1 times the hangar or deck space. The third GE T64-415 engine was mounted above and behind the housing for the starboard engine. The installation of a third engine necessitated extending the fuselage by six feet. Each engine could produce 4,380 shp and required a new 11,500 shp transmission system. The IRB developed for the CH-53D was adapted. A seventh blade was added to the main rotor and each blade was extended by three feet for a total increase in rotor diameter of six feet. The CH-53E is easily distinguishable from proceeding variants. The tail rotor pylon was canted at 20 degrees starboard to improve lift and the pylon was extended from 16 ft. to 20 ft. With the culmination of these features, the Super Stallion can carry external loads up to 32,000 lb. (14,515 kg) with an MTOW of 73,500 lb. (33,000 kg). Internally the CH-53E can accommodate up to 55 troops or 30,000 lb. of cargo. The Super Stallion can deliver a 32,000 lb. payload within a 50 nautical mile mission radius (58 miles or 93 km). The Super Stallion can accommodate 977 gallons of JP-5 fuel internally as well as 1,300 gallons of fuel in external tanks.

MH-53E

The MH-53E was developed from the CH-53E as an AMCM replacement for the RH-53D. The baseline Super Stallion airframe was modified with greatly expanded fuel sponsons for a total capacity of 3,212 gallons or 21,000 lb. of fuel. The expanded tanks give the MH-53E five hours of unrefueled endurance and a total range of 1,050 nm.

The Sea Dragon is fitted with a digital automatic flight control system with improved precision navigation and timing (PNT) equipment consisting of six accelerometers and five position sensors. The aircraft were later fitted with GPS as PNT equipment is critical to AMCM missions. Sea Dragons are routinely used for vertical replenishment and missions that require longer range and more precise navigation equipment than the CH-53E. The helicopter can lift an 8,000-lb. payload out to 500 nm. A hydraulic tow boom system rated to 30,000 lb. of tension is able to support a variety of AMCM systems.

Anti-Mine Countermeasure Equipment

The MH-53E’s AMCM mission systems have been modified over time. Sea Dragons typically take a mix of sensors to detect, sweep and neutralize mines based off of intelligence within that area. The MH-53E can accommodate the following towed sonars to detect mine-like objects in the water column: the Northrop Grumman ASQ-14, the Raytheon ASQ-20A, or the Northrop Grumman AQS-24A/AQS-24B.

Sweeping systems generally influence mines in preparation of neutralization. The Mk 103 mechanical system breaks tethered mines from their moorings. Detached mines are either neutralized by explosive ordnance disposal crews or the SLQ-60 Sea Fox mine neuralization system (previously done with crew-served 12.7 mm machine guns). The Sea Fox is an unmanned underwater vehicle (UUV) that can be fitted with a variety of sensors or an explosive charge. The Mk 104 acoustic system generates a sound field capable of actuating acoustic naval mines while the Mk 105 can detonate magnetic influence mines. The Mk 106 is a combination of both the Mk 104 and Mk 105 systems.

VH-53F

VIP variants assigned to HMX-1, the Marine Corps squadron responsible for the transportation of the President as well as staff and associated materiel. The VH-53D corresponds to the CH-53D model and the VH-53E corresponds to the CH-53E model. The VH-53F was a proposed configuration as of the FY1973 budget but the F model was not developed (refer to production & delivery history for more details).

CH-53G (S-65C-1)

The CH-53G is a license-produced copy of the CH-53D. All German CH-53s were originally delivered with GE T64-7 engines but were latter fitted with uprated, 4,330-shp-capable T64-100s. With T64s, the CH-53G has a MTOW of 50,000 lb. Additional information is available under upgrades section.

CH-53GS

The CH-53GS (German Special) configuration modified from the CH-53G with low-altitude flight modifications, night vision-compatible cockpit and Elbit Systems EloKa electronic warfare self-protection system consisting of a digital radar warning receiver and electronic warfare controller. Forward-deployed aircraft can be modified with supplemental ballistic protection, machine guns and dust filters.

CH-53GE

German Special Enhanced version, all features of the CH-53GS but with additional internal fuel capacity for increased range.

CH-53GA

The CH-53GA (Germany Advanced) configuration adds 4,000 hours of additional service life to each airframe (10,000 total), keeping the airframes viable to at least 2030. Additional features include a modernized flight control system with an automatic hovering mode and four-axis autopilot, Rockwell Collins cockpit suite with multifunction displays, improved self-protection system and SATCOM. The GA model can also accommodate a FLIR turret and auxiliary fuel tanks in the cargo compartment to reach ranges up to 746 miles (1,200 km).

HH-53H/MH-53H Pave Low III

The first HH-53H Pave Lows were modified HH-53Cs. Mission equipment included the Texas Instruments APQ-158 terrain-following radar (TFR), Canadian Marconi doppler navigation radar and Texas Instruments AAQ-10 forward-looking infrared (FLIR). The HH-53H also received uprated, 3,936-shp-capable GE T64-7A engines to offset performance penalties associated with the weight of the new mission systems. The airframes received structural modifications in the nose to enable installation of the new mission equipment. Provisions were also made for two 650-gallon auxiliary fuel tanks (up from 450 gallons). The HH-53H was latter redesignated as the MH-53H.

MH-53J Pave Low III Enhanced

The MH-53J Pave Low III Enhanced remanufacture process combined mission system and airframe upgrades with the shipboard operation program (SBO) and service life extension program (SLEP). The MH-53J introduced a host of avionics improvements such as a night vision-compatible cockpit, central avionics computer and modernized navigation system – with laser-ring gyroscope, doppler radar and inertial navigation system (INS). The aircraft were later fitted with GPS. Additional improvements were made to the aircraft’s APQ-158, FLIR and communications systems. The MH-53J’s survivability equipment consisted of the ALQ-162 self-protection jammer (H-J band) and the ALQ-157 infrared countermeasure system.

SBO modifications included an elastomeric main rotor head assembly with automatic main rotor blade and tail pylon folding system. To accommodate the airframe’s increased weight and shipborne operations, the MH-53J used reinforced landing gear from the RH-53D. SLEP modifications consisted of strengthened alloy tail pylon skins (without chemical milling), more robust accessory gearbox support structure, a new electrical wiring system and reinforced fuselage skins. Airframe weight grew substantially as a result of new mission systems, maritime compatibility modifications and additional titanium armor. Substantial structural modifications were required to meet the objective MTOW of 50,000 lb., up from 42,000 lb.

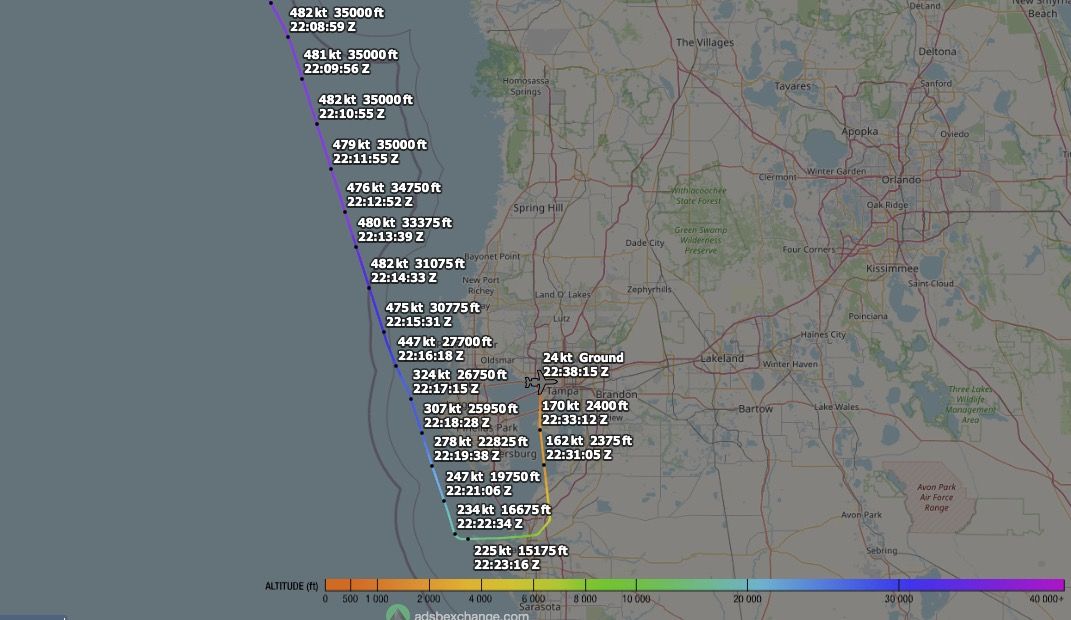

Despite the additional weight, the MH-53J was able to reach speeds up to 170 kts (197 mph or 315 km/h) and had a range up to 600 miles (967 km). Performance greatly improved as a result of the titanium composite IRB main rotor blades developed for the CH-53D, providing 2,000 lb. of additional lift. Furthermore, the T64-7A was replaced with the T64-100, which could provide a maximum of 4,330 shp each.

MH-53M Pave Low IV

The Pave Low IV configuration introduced the Interactive Defensive Avionics System/Multi-mission Advanced Tactical Terminal (IDAS/MATT) system. Near real-time threat data on enemy emitters, information about local power lines/obstacles as well as other information received via satellite was displayed on a digital map via NVG compatible multifunction displays. IDAS/MATT allowed MH-53M aircrews to navigate around hostile IADS and respond effectively if engaged. The M variant later was upgraded with the Northrop Grumman AAQ-24 directed infrared countermeasure (DIRCM) system.

MH-53K

The CH-53K “King Stallion” is the largest and newest derivative of the H-53 family and is designed to replace the CH-53E. The King Stallion has the highest design maximum gross weight of any helicopter produced outside of Russia, at 88,000 lb. (39,000 kg). However, the CH-53K has been tested to an MTOW of over 91,000 lb. The K model can carry external loads up to 36,000 lb. via an improved cargo hook system – single centerline, dual and triple hook configurations are available, enabling the aircraft to carry nearly all vehicles in the USMC inventory including:

- 1 x 10,000 lb. M777 Howitzer as well as several thousand lb. of ammunition

- 2 x 13,000 lb. up-armored HUMVEEs

- 2 x 16,000 lb. JLTVs, 40 nm in hot and high conditions

- 1 x 22,600 lb. up-armored JLTV

- 1 x 29,800 lb. M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS)

- 1 x 27,000 – 31,000 lb. LAV-25 (variant dependent)

While the E model can also lift payloads in excess of 30,000 lb., the K model’s defining trait is its range and endurance while transporting heavy loads. The CH-53K can carry a 27,000-lb. (12,247-kg) payload across a 110 nm (127 miles or 204 km) mission radius and return to its launch point under degraded conditions (outside air temperature of 95°F at 3,000 ft.).

For benchmarking purposes, the CH-53E can carry only 9,628 lb. (4,367 kg) under the same conditions. The CH-47F Block II will be able to carry a 16,000-lb. (7,258-kg) payload for 100 nm (115 miles or 185 km) with a 30-minute fuel reserve on a 95°F day at 4,000 ft. altitude. The CH-53K’s 30-ft. long internal cabin was widened by 12 inches over the E model (9-ft wide total), which allows for the internal carriage of one HUMVEE, two 463L pallets (10,000 lb. each), five half 463L pallets (5,000 lb. each), or six 40 x 48 wooden pallets (2,500 lb. each). Cargo loaded on standard USAF pallets can now be unloaded directly from C-17s, C-5s and C-130s and transferred to the CH-53K. On the prior E model, cargo had to be re-palletized from USAF cargo aircraft to 40 x 48 USMC standard pallets.

The CH-53K is able to achieve its heavy load range performance as a result of its new engines, rotor blades, fuel capacity and extensive use of composite materials. Compared to the GE T64, the GE T408-400 provides 57% more shp than the T64 (7,500 shp total), has 63% fewer parts and is 18% more fuel efficient. The King Stallion also features a multi-path, split-torque gearbox – enabling more even distribution of engine power across all three engines. The new composite main rotor consists of seven anhedral swept blades that are 35 ft long and nearly 3 ft. wide, totaling a surface area 12% greater than the E model’s rotors. The anhedral or swept tips provide significantly greater lift, improved speed and reduced noise compared to conventional rotor blades.

The King Stallion has a cruise speed of 150 kts (172 mph or 278 km/h) and maximum speed of 170 kts (196 mph or 315 km/h). The tail rotor is mounted to a 18° canted tail pylon and consists of four blades that feature a 15% increased surface area compared with the E model. The rear rotors provide as much thrust as the main rotors of a S-76 helicopter. The CH-53K has an internal fuel capacity of 2,286 gallons (8,653 liters) or approximately 15,545 lb. (7,095 kg) total in two side-mounted sponsons. With three 800-gallon fuel tanks mounted in the internal cargo compartment, the CH-53K can accommodate an additional 2,400 gallons (9,085 liters) or 16,320 lb. (7,450 kg). For comparison, the CH-47F Block II has a fuel capacity of 1,100 gallons and the G model Block II has a fuel capacity of 2,000 gallons. Like the MH-47G, the CH-53K has an inflight refueling probe to further extend the range of the aircraft as required.

The CH-53K’s airframe makes extensive use of composite materials across the aircraft’s skin, beam structures and cabin to reduce weight. Titanium and aluminum are also used on primary frames. The CH-53K has an empty weight of 43,750 lb. Unlike the E model, the K model features in-built ballistic protection in the crew compartment, cabin floor and side walls. The CH-53K also has greater survivability tolerances for key components such as 30-minute dry capable gear boxes and triple redundant fly-by-wire flight controls. The CH-53K’s full operational capability (FOC) survivability equipment includes:

- Northrop Grumman Large Aircraft Infrared Countermeasure (LAIRCM) directed infrared countermeasures (DIRCM) system with the improved Guardian Laser Transmitter Assembly (GLTA)

- BAE Systems ALE-47 countermeasures dispenser system

- Northrop Grumman APR-39D(V)2 radar warning receiver.

Testing found exhaust gases were interfering with the GLTAs and the devices will be removed for Initial Operational Test and Evaluation (IOT&E) and repositioned prior to FOC.

CH-53 Yas’ur 2000

Israeli remanufactured CH-53s that received an armored cockpit, crashworthy seats, aerial refueling probe, expanded fuel capacity, rescue hoist and new Elbit avionics and mission systems. Significant improvements were made to the aircraft’s cockpit with the addition of new computers, multifunction displays and a digital map. Elbit equipped the aircraft with its Elistra electronic countermeasures system. The type is powered by twin GE T64-413 engines rated to a maximum of 3,925 shp each.

CH-53 Yas’ur 2025

The performance upgrade consists of improved communications, navigation, self-protection systems and flight control system. An assortment of safety, reliability and maintainability enhancements will sustain the type until at least 2028 (originally 2025).

S-64C-2

Sikorsky designation of aircraft ordered by Austria, similar to CH-53Ds.

S-64C-3

Initial configuration ordered by Israel, similar to USMC CH-53Ds.

S-80M-1

Sikorsky export designation for MH-53Es produced for Japan. These aircraft have a similar configuration as their U.S. Navy counterparts but lack an inflight refueling probe.

Production & Delivery History

As of the time of this writing, more than 700 H-53s airframes have been produced – not including remanufactured aircraft. H-53s have been produced in two locations: Sikorsky’s production facility in Stratford, CT, and Vereinigte Flugtechnische Werke GmbH (VFW)-Fokker in Postfach, West Germany. Sikorsky started construction of its 800,000 sq.-ft Stratford plant in 1956. In 1980, the facility was greatly expanded to 2.2 million sq. ft. The same facility is used for the construction and assembly of the UH-60/S-70 Black Hawk. Sikorsky had considered moving CH-53K production toward either Florida or South Carolina.

United States

CH-53A

A total of 139 A models were produced between 1965 and 1968. Sikorsky production quickly shifted to the improved CH-53D. In 1988, the USMC had planned to completely phase out its CH-53A fleet by FY1991. By the end of operations in Desert Storm, the majority of CH-53As were out of service and disposed of.

HH-53B/HH-53C/CH-53C

In September of 1966, the USMC had loaned a pair of CH-53As to the USAF which tested their suitability for combat search and rescue (CSAR) operations. In 1967, the USAF drafted SEAOR #114, which issued requirements for a new combat aircrew recovery helicopter (CARA) to replace the earlier HH-3B “Jolly Green.” CARA would be capable of rescuing aircrews in all-weather environments as well as at night. The Air Staff decided an interim solution was needed to meet emerging search and rescue (SAR) capability shortfalls in Vietnam, which led to the HH-53B. The first aircraft took flight on March 15, 1967. Only eight HH-53Bs were built. In May 1968, Sikorsky was awarded a contract to develop a follow-on to the HH-53B to address shortfalls in demonstrated performance. The first HH-53C was delivered on Aug. 30, 1968. A total of 44 HH-53Cs were delivered to the USAF.

Concurrently, the USAF sought a transport derivative of the HH-53C to ferry heavy cargo and to transport SOF. U.S. Army CH-53s and USMC CH-53As were typically assigned to meet USAF in-theater requests, but the USAF sought its own heavy-lift helicopters to improve availability and reduce delays. In April 1968, Secretary of Defense Clark Clifford approved the procurement of a dozen CH-53Cs, with options for eight additional helicopters. The first CH-53C was delivered in March 1970 and subsequently transferred to the 21st Special Operations Squadron in August. The USAF exercised options for six of the eight helicopters, for a total order of 20 CH-53Cs, which were all delivered by the end of 1972. From 1967 to 1970, HH-53s were credited with rescuing 371 airmen. The last HH-53s and CH-53Cs were retired in 1990 as they were inducted into the MH-53J program.

CH-53D

Sikorsky produced126 USMC D models between 1968 and January 1972. The D model served in the USMC inventory for 43 years, from 1969 to 2012. The majority of retired airframes were transferred to Davis–Monthan Air Force Base, AZ, to Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (AMARG).

TH-53A & NCH-53A

In the 1980s, the Marine Corps agreed to transfer six CH-53As to the Air Force for training purposes. The aircraft were designated TH-53As upon entering Air Force service. The aircraft supported flight qualification training in support of the Pave Low program and were modified with machine guns to facilitate gunnery training.

The Marine Corps procured two CH-53As to support testing of the “Crested Rooster” retrieval system for Air Force Satellite Control Facility. Testing equipment was removed, and the aircraft were transferred to the Air Force to provide supplementary training capabilities along with the TH-53As.

RH-53A/RH-53D/MH-53D

The Marine Corps transferred 15 CH-53As to the Navy in 1971. The airframes were converted to the CH-53A configuration between 1971 and 1973 and were subsequently delivered to HM-12. However, the Navy came to view the T64-413 as underpowered and the RH-53A fleet was eventually returned to the CH-53A configuration.

The first RH-53D was delivered to the Navy in October 1972 and HM-12 transitioned to the RH-53D in August 1973. RH-53Ds participated in the failed rescue attempt of American hostages in Iran during Operation Eagle Claw on April 24, 1980. The mission plan called for eight RH-53Ds and USAF MC-130 and EC-130s to penetrate Iranian airspace and gather at a salt flat (Desert One) approximately 200 miles from Tehran. The RH-53Ds would refuel and transport 118 commandos to a location 65 miles from Tehran. The assault team would subsequently make their way to the embassy on day two and rescue the hostages. A minimum of six helicopters were required to execute the mission. However, two helicopters quickly had to return following flight instrument and mechanical problems. A third had hydraulic indicator issues on the way to Desert One, but the crew decided to continue the mission. That helicopter later broke down at the salt flat, which led to the decision to cancel the entire operation. As the five remaining aircraft were preparing to leave Desert One, an RH-53D struck an EC-130 while refueling, leading to the destruction of both aircraft. The remaining helicopters were abandoned inside Iran as the helicopter crews boarded the remaining EC-130s.

A total of 36 RH-53Ds were built between 1972 and 1977, including six for Iran via the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program. The RH-53D fleet was gradually withdrawn from U.S. service during the 1990s and replaced by the significantly more capable MH-53E.

Pave Low I, II, III (HH-53H)

The HH-53B/C was acquired between 1967 and 1972 as an urgent interim CSAR capability for Vietnam and was restricted to daytime-only operations. As early as 1965, the USAF had drafted requirements for an all-night and -weather CSAR capability. To rectify these shortcomings, the USAF launched the limited night vision recovery system (LNRS) in April 1968. The system included a radar altimeter, Low Light Level Television (LLLTV) camera, doppler navigation system, automatic approach, hover coupler system and infrared illuminator. Despite the system’s limitations, eight aircraft were modified and deployed with LNRS by January 1971. The more ambitious Pave Star program began in October 1968 but was truncated and replaced with the comparatively modest Pave Imp program in 1971. Pave Imp produced the Night Recovery System (NRS), which was more effective than LNRS, but the service still lacked all-weather, nighttime, penetrating CSAR capability. The Pave Low program was launched to fully meet service requirements in June 1970. “Pave” is an acronym for precision avionics vectoring equipment, and “Low” corresponds with the low altitude mission.

The resulting aircraft from the Pave Low program would need to be able to conduct nap-of-the-earth (NoE) flights to survive penetration missions in environments with increasingly capable integrated air defense systems (IADS). The aircraft would require a terrain-following radar (TFR), highly accurate navigation equipment and night vision equipment. The USMC had experimented with a CH-53A fitted with a Norden TFR in 1968 to provide an all-weather capability, but the system never progressed past trials. From April to December 1972, USAF personnel at Edwards AFB tested a HH-53B fitted with both the Norden APQ-141 and LNRS. The APQ-141 was developed for Army’s AH-56 Cheyenne attack helicopter and numerous issues were identified during the Pave Low program. The Pave Low II program was subsequently launched with the goal of developing a new radar system capable of low-altitude penetration (minimum of 200 ft.) with terrain collision avoidance as well as greatly improved navigation equipment. Cost growth in the program to modify eight aircraft grew from $14.2 million to $20 million ($76.6 million and $107.5 million in 2020 dollars, respectively) in 1974, leading to the Pave Low III program, which sought to accomplish the same mission with off-the-shelf components.

The YHH-53H Black Knight prototype was fitted with T64-7A engines, Texas Instruments APQ-126 terrain-following radar (from the Navy’s A-7 attack aircraft), doppler radar from Canadian Marconi and a Texas Instruments AAQ-10 FLIR. Production-configuration aircraft would receive the APQ-158 TFR, which was adapted to enable low-level fight to 100 ft. above ground level vs. the APQ-126’s 200 ft. Flight testing began in 1975 and in 1977 the USAF ordered the modification of eight HH-53Cs to the Pave Low III configuration. All Pave Low III modified aircraft would be redesignated HH-53Hs. The first HH-53H was delivered to Military Airlift Command in April 1979. The prime contractor for the Pave Low III modification was Naval Air Rework Facility (NARF) at Pensacola Naval Air Station (NAS), FL.

Pave Lows were stated to be used for the second attempt at rescuing the American embassy hostages (Operation Honey Badger) in 1980 following the poor performance of the RH-53D. In 1986, a pair of CH-53Cs were modified to the HH-53H as attrition replacements for a pair of aircraft lost in 1984. A total of 11 HH-53Hs were produced, including one prototype. As the Pave Low’s primary mission changed to special operations transport the helicopter was redesignated the type to the MH-53H in 1986. Eight aircraft would remain in service prior to the MH-53J conversion program.

MH-53J Pave Low III Enhanced

Traction gradually grew within the Air Force to fully utilize the aircraft for long-range special operations infiltration and exfiltration missions. The MH-53J Pave Low III Enhanced configuration was developed with SOF as the primary mission rather than CSAR. In August 1985, Military Airlift Command (MAC) requested funding to modify and extend the service lives of the remaining HH-53Hs as well as 25 HH-53s and CH-53Cs to the Pave Low III Enhanced configuration. The first MH-53J was rolled out in July 1987. By this time, the USAF had 41 H-53s of 12 distinct configurations. In 1988, Congress approved the USAF to modify its entire H-53 fleet to a common MH-53J standard. MH-53Js were subsequently transferred to Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) in 1990. Conversion and SLEP work at NARF Pensacola was completed by the end of 1995.

MH-53M Pave Low IV

In April 1998, AFSOC received its first IDAS/MATT-equipped MH-53J. Equipped aircraft were subsequently redesignated MH-53Ms to highlight the importance of the IADS/MATT system. The “M” designation was selected instead of the sequential “K” as USSOCOM operated the MH-60K. A total of 25 MH-53Js were upgraded to the MH-53M configuration by the end of 2001. The last Pave Low was withdrawn from operational service in 2008 and replaced with the Bell-Boeing CV-22 Osprey. Retired aircraft were stored at Davis-Monthan AFB.

CH-53E

Over the course of the CH-53A & CH-53D Sea Stallion’s service life, the Marine Corps placed progressively greater demands on the platform. On Oct. 24, 1967, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) approved SOR-14-20, which called for a new heavy-lift helicopter for both the Navy and Marine Corps. SOR-14-20 called for a helicopter that would be able to carry an 18-ton payload at a speed of 125 knots (144 mph or 232 km/h). The Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) attempted to merge the program with an Army heavy lift program but was ultimately unsuccessful as Army requirements were irreconcilable with maritime operations. Sikorsky had begun studying three engine configurations of the CH-53 in 1968, which enabled the company to successfully market its design as a lower-risk proposal when the inter-service program collapsed in 1971. In November 1971, the DoD authorized the production of two YCH-53 prototypes. The CH-53E was procured as an engineering change proposal (ECP) to the RH-53D to avoid another drawn-out procurement.

The first YCH-53E took flight in March 1974 and testing continued throughout the decade. Sikorsky built two YCH-53E prototypes, a static test airframe and a pair of CH-53E production representative test articles. The USMC concluded initial service acceptance trials of the CH-53E at Naval Air Station Patuxent River in March 1977. In February 1978, the Navy issued a production contract for half a dozen Super Stallions. The first production aircraft took flight in December 1980 and was delivered to the USMC in June the following year.

Initially, the Department of the Navy (DoN) sought to procure 70 Super Stallions, with half going to the Marine Corps and half to the Navy. The latter subsequently opted to fund the fixed-wing C-2 for carrier onboard delivery missions and reduced the total DoN buy to 49 airframes. However, the program of record (POR) soon grew from 49 to 126 to approximately 160 by 1982. On March 11, 1983, Helicopter Mine Countermeasures Squadron 12 (HM-12) received the Navy’s first CH-53E for use in vertical onboard delivery (VOD). Helicopter Support Squadron Four subsequently took delivery of CH-53Es in May 1983 and was followed by HC-1 in January 1984. HC-4 became the Navy’s first and only dedicated CH-53E squadron and had a fleet of eight aircraft by 1990.

In FY1985, the Navy requested to base further production contracts off of Multi-Year Procurements (MYP). At that time, the DoN had taken delivery of 63 Super Stallions. The DoN had requested 281 CH-53Es and MH-53Es in FY1984 and 287 helicopters in FY1985, but Congress had only funded the procurement of 232. The resulting FY1986-1989 MYP covered 56 helicopters—27 CH-53Es and 29 MH-53Es. By April 1988, the Marine Corps had taken delivery of 80 Super Stallions, of which 75 were operational. The Navy had taken delivery of 16 CH-53Es for VOD missions, of which 15 were operational.

By FY1990, the USMC had reduced its CH-53E request to 191 Super Stallions. The flyaway cost of a CH-53E in FY1990 was $20.7 million or $42.7 in 2020 dollars. The majority of CH-53Es were delivered by the end of 1993 with intermittent deliveries continuing until October 1999, when Sikorsky delivered the last Super Stallion to the Marine Corps.

U.S. Navy Super Stallions were gradually phased out of service and transferred to AMARG and the Marine Corps from the 1990s to early 2000s. In February 1995, HC-4 began to phase out its Super Stallion fleet as it transitioned to the Sea Dragon, which would take over the VOD missions in addition to its AMCM role. The Navy’s had a single CH-53E in service as of April 2003. Press reporting in November 2003 indicated the Marine Corps received its “last” CH-53E – some four years after the production line had closed. However, a number of CH-53Es at AMARG were restored and transferred to the Marine Corps. In July 2006, the Marine Corps took delivery of its first regenerated CH-53E – a former HC-4 USN aircraft. A total of eight CH-53Es had been placed in storage at AMARG with one returned to active service and four additional airframes slated to be restored. As of June 2020, seven former USN CH-53Es are in active service with the Marine Corps.

A total of 180 production-configuration aircraft were delivered along with two YCH-53Es and two production-representative test articles, for a total of 184 aircraft. As of this writing, 142 remain in service with the USMC.

MH-53E

A single YCH-53E test aircraft was permanently converted to serve as an MH-53E demonstrator. The helicopter was subsequently redesignated as an NMH-53E and first flew in September 1983. At that time, the Navy had a POR for 51 MH-53Es to replace its RH-53D fleet.

The HM-12 “Sea Dragons,” from which the MH-53E got its nickname name, took delivery of the first production configuration MH-53E on May 28, 1987. A total of 47 production-quality aircraft were manufactured, with the last airframe delivered in September 1994. The NCH-53E prototype was struck from the naval register in 1999. MH-53Es are service in two AMCM squadrons, HM-14 & HM-15, as well as one fleet reserve squadron. In 2015, the Japanese Ministry of Defense announced it would transfer its S-80M-1 fleet to the U.S. which would return a pair of aircraft to service and use the remaining airframes for spare parts. Erickson Aviation was scheduled to deliver this aircraft by the end of 2018. As of November 2021, 30 MH-53E Sea Dragons remain in service.

The MH-53E fleet was planned for retirement in the mid-2000s but the Navy concluded the MH-60S Sea Hawk could not directly replace the Sea Dragon given the former’s much greater range and endurance. The MH-53E will be indirectly replaced by the Littoral Combat Ship’s mine countermeasure mission package. The secondary onboard delivery mission will be subsumed by the CMV-22 and the Navy will keep the MH-53E in service through 2025.

VH-53F

The FY1973 budget requested six VH-53F helicopters. In 1974, the military assistant to the President and the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense notified the Navy that 11 VH-3Ds would better meet HMX-1 requirements at approximately the same cost ($29.6 million or $163 million in 2020 dollars). A significant contributing factor toward the decision to cancel the VH-53F was the helicopter’s significantly greater size and rotor downwash when compared to the VH-3D.

CH-53K

As part of the Operational Maneuver from the Sea (OMFT) and Ship To Objective Maneuver (STOM) concepts, Marine Air Ground Task Groups seek to project power deep inland and directly bypass the beach. As originally envisioned upon entering service in 1981, the CH-53E would lift heavy equipment while the smaller CH-46 would transport personnel. In practice, both assets struggled to help the MAGTF project power deep inland given their limited range in their heavier assault and transport configurations. The CH-46 had a mission radius of 50 to 70 nautical miles with 10 to 15 combat-laden troops. The CH-46’s limitations were so severe that the assault transport role was effectively taken over by the CH-53D and CH-53E fleet its later years – adding to the strain of the Stallion fleet. The CH-53E could lift nearly all the heavy equipment in the Marine Corps inventory except the M1A1 Abrams and AAV-7, but only for a distance of 50 nautical miles. High operational use of the CH-53E fleet and range concerns led to the CH-53X program.

The CH-53X concept was originally conceptualized as a CH-53E remanufacture program. The airframes would be return to service in “like new” condition but with upgrades to the engines, rotor blades and relatability and maintainability upgrades. Around this time, the DoD had sought to develop a joint heavy-lift solution to meet Army and Marine Corps needs in the early 2000s, but the Marine Corps quickly decided it could not wait for a joint solution to materialize. An analysis of alternatives (AoA) was completed in September 2003 and examined seven existing aircraft designs.

The study found that a heavily modified CH-53E was the only aircraft available that could meet service requirements. Four distinct CH-53E configurations were examined. The study concluded that building a new airframe was the most cost-effective solution, resulting in the Heavy Lift Replacement (HLR) program. At that time, the Navy intended to procure 154 HLR aircraft, with a sole-source contract to Sikorsky to accelerate the acquisition. Under these plans, various subcomponents of the helicopter—such as engines—would be competed to lower costs. Under the original schedule, the first EMD test article would fly in FY2012 and the Marine Corps would declare initial operational capability (IOC) in 2015.

The Operational Requirements Document (ORD) was approve by the JROC and was signed in December 2004. A key performance parameter (KFP) within the ORD was the ability to carry an approximately 15-ton payload within a 110 nm radius in a degraded operating environment – effectively meeting STOM requirements to carry a LAV-25 or two up-armored Humvees with a 3,000-lb. margin. These requirements would be relaxed to 27,000 lb. later on in the program. NAVAIR awarded Sikorsky a $34 million contract for requirement definition and engineering studies in December 2004. Sikorsky was awarded a $3.04 billion ($3.92 billion in 2020 dollars) contract for System Development and Demonstration (SDD) in April 2006. Sikorsky selected GE to provide GE38-1B engines for the CH-53K in January 2007. The CH-53K preliminary design review (PDR) process began in June 2007 and concluded in September 2008. In 2008, the USMC raised its POR from 156 to 200 CH-53Ks. The King Stallion’s Critical Design Review (CDR) concluded in June 2010.

Four Engineering Development Model (EDM) aircraft would be built to support SDD. These aircraft are designated as YCH-53Ks and are referred to as EDM 1-4. The EDM aircraft were manufactured at Sikorsky’s facility in Palm Beach, FL. The first helicopter first took flight on Oct. 27, 2015, and EDM-4 took flight on Aug. 31, 2016. In May 2013, Sikorsky was awarded $435 million to build four System Demonstration Test Article (SDTA) aircraft with Research Testing Development and Evaluation (RTD&E) funds. Another pair of SDTA helicopters were awarded in September 2016 for $232 million.

SDTA-configuration aircraft bridge the gap between SDD airframes and serial production aircraft. All of the EDM and the first pair of SDTA aircraft were assembled in West Palm Beach, FL. In 2016, Sikorsky decided future assembly would be performed in Stratford, CT. In May 2018, the USMC took delivery of its first RTD&E aircraft—STDA-3—at MCAS New River, NC. The aircraft will be used to inform maintenance and sustainment procedures and initial test and evaluation (IOT&E). As of September 2019, four EDM and two SDTA aircraft are in developmental flight testing at NAS Patuxent River, MD. The third SDTA K model had completed a supportability test and evaluation Logistics Demonstration (LOGDEMO) at MCAS New River. As of the FY2021 PBR, the fourth STDA is due to deliver to the USMC in calendar year (CY) 2020, followed by the fifth and six airframes in CY21.

The Defense Acquisition Board granted Milestone C approval for the production of up to 26 low rate initial production (LRIP) aircraft in April 2017. LRIP Lot 1 followed in August of that year, covering a pair of aircraft for $304 million. Sikorsky was awarded a contract for five Lot 2 and seven Lot 3 LRIP production CH-53Ks on May 17, 2019, worth $1.3 billion. The FY2021 PBR notes Lot 4 will consist of six aircraft. Sikorsky has faced delays with 126 deficiencies identified throughout flight testing that must be addressed prior to IOC, the most serious of which was exhaust gas reingestion (EGR). The No.2 and No. 3 engines were ingesting hot exhaust gases back into engine inlet, causing increased lifecycle costs, decreasing time-on-wing and potentially engine overheating and stalls. EGR is a frequent problem in the development of three-engine helicopters and was addressed in the preceding Super Stallion.

The Marine Corps submitted an Above Threshold Reprogramming (ATR) request to Congress in January 2019 for $158 million. Development overruns for testing left insufficient funding to continue work on SDTA 5 and 6. In February 2019, Congress approved a reprograming request for $79 million in FY2019 RDT&E funding from the H-1 to the CH-53K program. A joint industry and government team began work on an EGR solution in April 2019 and concluded work in December of that year. NAVAIR announced a total of 135 potential configurations were examined with respect to engine performance, survivability, materials, structures, logistics, system safety, reliability and maintainability. Gen. Rudder testified before Congress in March 2020 and stated the EGR solution would be incorporated into LRIP Lot 2 production aircraft, but Sikorsky later clarified that the pair of LRIP Lot 1 aircraft would also feature the EGR solution.

As of the FY2022 PBR, a total of 205 CH-53K airframes will be built: one Ground Test Vehicle (GTV), four EDMs, four SDTAs and 196 production-configuration aircraft. The total program cost is estimated at $34.036 billion in FY2021 dollars, according to the SAR. The report estimates a total procurement cost of $25.925 billion and an average flyaway cost of $114.86 million. The Full Rate Production (RFP) decision review changed from September 2020 to November 2022. IOC is planned for September 2021 and Full Operational Capability is planned for 2029. The FY22 Navy budget requests $1.47 billion for nine aircraft.

In March 2020, reporting emerged that Gen. Berger, commandant of the Marine Corps, was proposing a sweeping restructure to its future force, emphasizing long-range precision fires, unmanned aerial vehicles and cargo transports. Under the ten-year plan, the number of heavy-lift squadrons would be reduced from eight to five. Under the previous FY2019 Marine Corps Aviation Plan, each heavy-lift CH-53K squadron contained 16 aircraft. Note the five to eight squadrons of CH-53Ks would only correspond to Primary Mission Aircraft Inventory (PMAI) airframes. The Total Aircraft Inventory (TAI), encompassing the entire procurement under the POR, contains training, attrition reserve and other non-PMAI category airframes. Previous plans also stated USMC requirements called for 20 additional aircraft beyond what is funded in the PBR.

On June 25, 2021, NAVAIR awarded Sikorsky $878.7 million for Lot 5 production for nine CH-53Ks. The contract also included an option for Lot 6 production worth $852.5 million which is expected to be exercised in Q1 of 2022 using FY22 funds. In September 2021, Sikorsky delivered the first operational CH-53K to HMHT-302 Squadron.

Austria

The Austrian Air Force received a pair of S-65C-2 (equivalent to the CH-53D) helicopters, which were produced in 1969. High operating costs eventually led the service to transfer its aircraft to the Israeli Air Force in 1981.

Iran

RH-53D

Prior to the revolution of 1979, Iran acquired half a dozen RH-53Ds for AMCM through the FMS program. The Islamic Republic of Iran later acquired the five abandoned U.S. Navy RH-53Ds, which participated in Operation Eagle Claw. These airframes were used for spares to sustain its first installment of aircraft. As of the time of this writing, four aircraft are believed to be in operational condition.

Israel

S-65C-3/CH-53D

As early as the 1950s, the Israeli Air Force (IAF) sought a heavy assault helicopter capable of ferrying paratroops across long distances while also lifting oversized cargo, freeing up fixed-wing transport assets. The IAF acquired Sikorsky S-58Bs in 1957 but soon found the helicopter was largely unable to perform the desired role. Aerospatiale Super Frelon’s were acquired from France that would latter see extensive service in the Six Day War of 1967. IAF Super Frelons performed critical transport, resupply and medevac missions.

Looking to build on this capacity, the IAF sent a delegation to the United States to examine both the Boeing-Vetrol CH-47 Chinook and Sikorsky CH-53 Sea Stallion in 1968. Ultimately, the team selected the S-65C-3 (similar to the CH-53D configuration) with an initial order of seven aircraft. The first began to arrive in Israel in October 1969. Israel later placed follow-on orders, bringing the total number of new-build aircraft to 35 by 1975. Israel also received several batches of secondhand H-53s, including:

- 8 USMC CH-53As in 1973

- 2 Austrian S-65C-2s

- 10 USMC CH-53As between 1991-1992

- 8 USMC CH-53s between 1993-1993 (but not used)

- 5 USMC CH-53Ds for spares in 2013

Not all of these aircraft were used for active operation; several were used as a source for spare parts and rendered inoperable. Israel transferred four of these aircraft to Mexico between 2005 and 2006 The aircraft were named “Yas’ur” upon entering service, meaning Petrel in Hebrew.

CH-53 Yas’ur 2000

In the 1980s, the IAF looked at upgrading and sustaining its CH-53 fleet such that it could remain in operation past 2000. Elbit was selected to upgrade the aircraft’s avionics and mission systems to include multifunction displays, computers and head-up display. The first aircraft made its first flight in June 1992 and the first aircraft was delivered in August 1993. A total of 37 aircraft were remanufactured by the end of 1997.

CH-53 Yas’ur 2025

Between 2006 and 2015, the IAF upgraded its CH-53 fleet to the Yas’ur 2025 standard. According to the IAF, the retrofits cost approximately $2 million per airframe. The type is expected to serve until at least 2028 while Israel considers a heavy-lift replacement program. As of May 2020, the tender includes the Boeing CH-47F and Sikorsky CH-53K.

CH-53K

Israel’s Ministry of Defense on February 25 selected the Sikorsky CH-53K heavy-lift helicopter over the Boeing CH-47F Block II to replace a fleet of 23 CH-53s. “The new helicopter is adapted to the [Israel Air Force’s] operational requirements and to the challenges of the changing battlefield,” said Defense Minister Bennie Gantz. The selection ends a lengthy competition within Israel between the two U.S. heavy lift helicopter options. The announcement also completes a series of long-delayed military procurement decisions in Tel Aviv. The IDF has long held a preference for larger, more capable rotary wing platforms dating as far back as the use of Super Frelons during the Six Day War in 1967 for special operations forces, search and rescue and general transport

In July 2021, the DSCA issued a notification regarding the potential sale of 18 CH-53Ks along with associated equipment and support services worth $3.4 billion. In August 2021, H-53 Program Manager Col. Perrin announced Israel is likely to take delivery of its first CH-53Ks between 2025-2026. Furthermore, the order for 18 aircraft is actually an order for 12 helicopters with an option for a further six airframes.

Germany

CH-53G

West Germany was an early participant in the CH-53 program. The first German pre-production example took flight in 1969 and deliveries began in 1972. A total of 112 CH-53Gs were produced with 110 produced under license by Vereinigte Flugtechnische Werke GmbH. The first 20 locally assembled aircraft were built from Sikorsky supplied kits. GE delivered its first T64-7 engines to Germany in 1971; subsequent production was undertaken by Klöckner-Humboldt-Deutz (KHD) and MTU, which delivered all 247 engines by 1975.

As part of a larger structural reform within the Bundeswehr (German Military), the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) transferred its UH-1s and NH90s to the Heer (German Army) in return for its inventory of CH-53Gs in 2013. Germany has gradually drawn down its CH-53 fleet from 98 in 2009 to 89 in 2012. In response to Bundestag inquires, the Bundeswehr announced in May 2019 that the Luftwaffe had a total of 71 CH-53s, of which 48.5 were available and 21.8 ready for use at any time. Prior plans called for the fleet to be reduced to 66 aircraft by 2014.

In addition to the Luftwaffe, a pair of CH-53Gs are operated Wehrtechnische Dienststelle 61 (WTD 61, Defense Technical Department 61) under the Bundesamt für Ausrüstung, Informationstechnik und Nutzung der Bundeswehr (BAAINBw, or Federal Office of Bundeswehr Equipment, Information Technology and In-Service Support).

CH-53GS/CH-53GE

From 1999 to 2001, 20 CH-53Gs were modified to the CH-53GS configuration. An additional six Gs were upgraded to CH-53GEs. In February 2017, BAAINBw contracted the upgrade of 26 helicopters to replace obsolescent parts such as the navigation, flight control and communications systems, as well as the installation of mode 5 identification friend or foe (IFF) capability. The contract covers a pair of CH-53GS to be used as demonstrators, plus 18 CH-53GS and 6 CH-53GE series production helicopters. The program is expected to run through 2022 at a total cost €135 million. In February 2020, BAAINBw announced it had contracted Elbit Systems to upgrade the GS/GE fleet with modernized self-protection equipment.

CH-53GA

As early as 2006, the Bundeswehr was interested in fielding a major SLEP & modernization upgrade to its CH-53 fleet. By this time, the German CH-53 fleet had experienced 36 years of continuous service. In 2007, EADS was awarded a €520 million ($690 in adjusted 2020 dollars) contract to upgrade 40 CH-53Gs to the GA standard and extend the fleet until 2030. The first aircraft took flight in February 2010 and was delivered in 2012. The last aircraft was delivered by the end of 2017, by which time BAAINBw reported costs for the program had increased by €102 million ($112 million), or 20% higher than the original estimate.

CH-53K (Competition)

The CH-53K and CH-47F are competing for a German Air Force requirement for 44-60 helicopters. In September 2020, BAAINBw judged the tender in its current form to be uneconomical because bids were well in excess of the €5.4 billion ($6.5 billion) budget allocated by Berlin. At the end of January, it emerged that Germany begun soliciting bids for the two helicopters through the U.S. Foreign Military Sales process. The underlying requirement is still viewed as among Germany's highest modernization priorities and deliveries are still expected by the end of the decade.

Japan

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) obtained license to produce both the CH-53E and MH-53E. However, extensive delays and inflation led to the Japan Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF) ordering just 11 helicopters despite a requirement for 12. The contract for 11 aircraft was awarded in 1987 and Japan’s first S-80M-1 was delivered in 1989. The fleet was withdrawn from service and replaced with MCH-101s in the AMCM role by March 2017.

Mexico

As part of a broader, $90 million arms deal in 2003, the Mexican Air Force ordered four secondhand Israeli CH-53’s that had been upgraded to the Yas’ur 2000 configuration. The first pair were delivered by July 2005 and the next by April 2006. The aircraft were withdrawn from use by the end of 2015.

Upgrades

CH-53E Engine Upgrades

As of the time of this writing, the USMC CH-53E fleet consists of three separate engine configurations featuring either the T64-416, T64-416A or T64-419. In FY2005, the Marine Corps began modifying its baseline 416 engines to the 416A configuration through the Engine Reliability and Improvement Program (ERIP). T64-416 engines are fitted with more durable internal components such as improved shrouds, blades, etc., which result in longer engine life and greater reliability. The FY2017 PBR reported that 416 of the 460 engines were upgraded to the 416A configuration at that time.

The second stage upgrades the 416A to the 419 configuration, which improves performance and commonality with the Navy MH-53E fleet. As of June 2020, 86 aircraft have been upgraded with T64-419 engines across the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing (MAW). The Marine Corps is evaluating the remaining schedule to accommodate force design impacts on the CH-53E program and the CH-53K transition. Additionally, the Marine Corps is pursuing new 419 engine cores and fuel control units to regain capability and increase readiness. The FY21 request contains $834.3 million for this effort across the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP) through 2025. T64 depot maintenance work is conducted at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, NC.

CH-53E Reset

USMC Super Stallions have been in continuous operational service for nearly 40 years as of the time of this writing. CH-53E availability and safety have been greatly affected by both the aircraft’s age and exhaustive use. Key components limiting the Super Station’s design life include the main transmission beams, bulkheads and vertical pylon components. The pylon has a design life of 6,120 hours. Planned depot maintenance was often delayed, sustaining high operational demands in Iraq and Afghanistan. Aircraft would stay in CENTCOM for years while crews would rotate in theater. In 2005, the Navy confirmed that Marine CH-53Es had experienced twice the anticipated attrition over the course of their service lives from mishaps. By 2016, readiness had fallen to 23%.

The USMC began the CH-53E Reset program in 2016 to rectify these issues. The process takes 110 days per airframe and involves completely stripping components and rebuilding the aircraft. As of July 2019, 25 CH-53Es have completed the Reset process, which will sustain the fleet until 2032.

MH-53E FLEXt

The Sea Dragon fleet had similarly seen high operational use with aging components. The Sea Dragon fleet began reaching the end of their service lives in FY2007. The Fatigue Life Extension Program (FLEX) increased the service life of each airframe from 6,900 flight hours to 10,000. The program extends the fleet through 2025 at a cost of $500,000 per helicopter.

CH-53E Surviability Equipment

The Super Stallion has been upgraded with modern aircraft survivability equipment (ASE) over the course of its service life. Current-configuration aircraft are fitted with the AAQ-24(V)6 large aircraft infrared countermeasures (LAIRCM) DIRCM, Northrop Grumman AAR-47(V)2, BAE Systems ALE-47 countermeasures dispenser system and Northrop Grumman APR-39(D)V2 radar warning receiver.

CH-53G Engine Upgrades

MTU began testing three the T64-100s in 1999. Germany placed its first order for 46 T64 retrofit kits in 2003. The retrofit process required extensive modifications of nearly a dozen components such as the combustor inserts, gas generator turbine and fuel pump. MTU delved the 166th and final upgraded engine in October 2014.

admin

admin